Bartels Explainer

How did President Alvarado’s policies protect Costa Rica’s environment?

Viviana Ruiz-Gutierrez talks about her recent biodiversity assessment and how Alvarado’s policies engaged citizens in climate action.

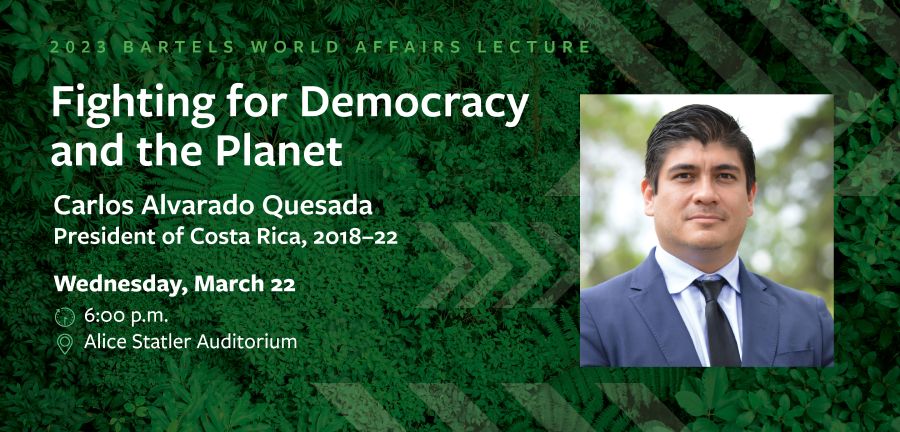

This year’s Bartels lecturer, President Carlos Alvarado Quesada (2018–22), started Costa Rica on track to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 with an ambitious climate action plan to meet the objectives of the United Nations’ 2015 Paris Agreement. His administration’s climate and conservation policies earned Costa Rica the 2019 Champion of the Earth Award, the UN’s highest environmental honor.

"We found significant biodiversity losses in regions with high-impact agriculture."

On this page: Viviana Ruiz-Gutierrez describes Costa Rica's unique standing as a global biodiversity hotspot with a long history of environmental regulations—not always effectively enforced—and explains how Alvarado’s policies enlisted Costa Ricans in climate action. A native of Costa Rica, Ruiz-Gutierrez is co-director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Center for Avian Population Studies, conservation science program leader, and a fellow at Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

Coming March 22: Reserve Your Free Ticket Today!

A Conversation with Viviana Ruiz-Gutierrez

Did Alvarado reverse any damaging environmental policy trends in his time in office?

President Alvarado sought to balance the pressures to increase growth and development in Costa Rica while protecting our natural capital. A notable example was when he vetoed a project that would have authorized shrimp trawl fishing in Costa Rican waters—an activity that would negatively impact small-scale fishermen and destroy marine life.

Another success of the Alvarado administration was the Escazu Agreement, which was signed in Costa Rica in 2018 and took effect in 2021. The agreement provided a sweeping framework to promote inclusive, informed, and participatory climate action in Latin America and imposed requirements to protect the rights of environmental defenders in the region.

Unfortunately, current president Rodrigo Chaves has taken steps to potentially reactivate shrimp trawling in the country and, in February, pulled back Costa Rica from the UN-backed climate agreement.

What kinds of changes to wildlife habitats have you observed in Costa Rica?

In my own research with the Lab of O’s conservation science program, we recently completed a biodiversity assessment for the country using birds as indicators. Our results support current knowledge—and my own observations that Costa Rica has successfully preserved much of its biodiversity through the National System of Conservation Areas.

However, we found significant biodiversity losses in regions with high-impact agriculture and where unregulated urban development has degraded and impacted forest remnants.

How did Costa Rica start to make conservation a priority?

Costa Rica’s achievements in conservation and environmental issues can be traced back to the country’s most politically relevant decision—abolishing the army in 1949. This decision is what has allowed Costa Rica to spend social capital on environmental issues for the past 74 years.

A few key laws in the 1990s have served as the backbone for biodiversity conservation. In 1994 the constitution was amended to state that “every person has the right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment.” The 1996 Forest Law mandates the rational use of all natural resources, prohibits land-cover change in forests, and includes incentives like the Payment for Ecosystem Services Program. Unfortunately, enforcement of these laws has varied widely among different governments.

What’s one practical step Alvarado’s administration took to encourage citizens’ participation in conservation?

The participation of citizens in conservation action at local levels is a critical driver for different initiatives. One example is the decarbonization plan launched by Alvarado’s administration in 2019, which aims for a decarbonized economy with net-zero emissions by 2050.

A big component of Alvarado’s plan was to renew the transport system, which is the country’s major source of greenhouse emissions. This included the goal of full electrification of all buses and taxis and incentives to move 100 percent of light-duty vehicle sales to zero emissions by 2050. Any changes to the transport system require significant buy-in and participation from citizens.

As a result of tax exemptions, many people purchased new or used electric vehicles. Charging stations became more common across the main central valley. These changes were starting to gain momentum when the pandemic hit, and the economic impacts and controversies surrounding the pandemic diverted public attention and support.

Has Alvarado’s successor continued the 2050 plan?

Rodrigo Chaves’ administration has not made the plan a priority. Alvarado’s plan included significant measures in basic infrastructure and economic sectors, such as public and private transport, energy, industry, agriculture, waste management, and soil and forest management. Many of these measures have fallen by the wayside.

Chaves has allowed the public bus sector to retain fleets of older buses, for example—compromising not just the goals of the plan, but the health of the people and ecosystems of Costa Rica.

Don't miss the Bartels World Affairs Lecture with Carlos Alvarado Quesada on March 22: Reserve your free ticket today!