Labor, Migration, and the Philippine Radical Tradition of Theatre

A reflection by SEAP faculty member Christine Balance, on a June 4th screening of Magno Rubio.

Dawn Bohulano Mabalon was a historian whose work centered on the lives, stories, and culture of manongs (older brothers or uncles) – migrant Filipino laborers who first arrived and settled in the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century. Manang Dawn, as she is lovingly known among her family and friends, was one of the first Filipinas to show me that a life of scholarly pursuit was possible. During the late 1990s, living in San Francisco, we would often work together at cafes and in her apartment – me studying for the GRE and preparing grad school applications while she read through the enormous binders of articles and notes she gathered for her PhD qualifying exams at Stanford University. From those days until her untimely passing in August 2018, Manang Dawn modeled for me ways of research, teaching, and community organizing steeped in a deep love and care for Filipino America.

Dawn Bohulano Mabalon at Little Manila is in the Heart book launch and signing (July 2013, Stockton, CA)

Dawn was the daughter of an actual manong, Ernesto Mabalon, and the granddaughter of Pablo “Ambo” Mabalon, owner of the Lafayette Lunch Counter, a restaurant/diner opened in Stockton’s Little Manila in the 1930s. It was not until she was an undergraduate at UCLA, taking her first Pilipino Studies course with Royal “Uncle Roy” Morales and reading Carlos Bulosan’s canonical novel America is in the Heart, that she realized the historical significance of her lolo’s (grandfather’s) restaurant as well as her hometown.As Dawn wrote in the introduction to her Little Manila is in the Heart: the Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California, when she asked her father about Bulosan after reading his novel, she learned that the famed Filipino writer used the Lafayette Lunch Counter as his permanent address and was gifted free meals by Lolo Ambo who “couldn’t bear to see Filipinas/os starve.” Skeptical of her father’s story, the intrepid young scholar researched Bulosan’s archive at the University of Washington, finding a letter from one of Bulosan’s girlfriends who mentioned sending correspondence via “Pablo” in Stockton. “Suddenly, my father’s memories became history, corroborated by archival evidence, and framed by my deeper understanding and embrace of my hometown’s Filipina/o American history.

Right: Pablo 'Ambo' Mabalon (left), Dawn Mabalon's grandfather, stands in front of his Lafayette Lunch Counter, which was in the heart of Little Manila. (Courtesy Little Manila Rising)

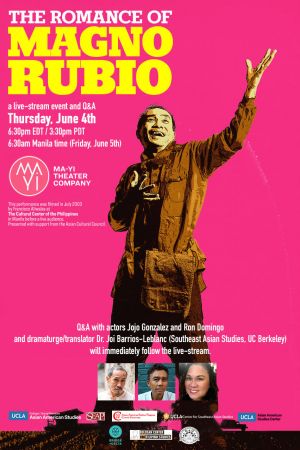

In October 2008, Dawn worked to bring Bulosan back to Stockton’s Little Manila, helping to produce The Romance of Magno Rubio’s two benefit performances on behalf of the Little Manila Foundation, an organization she co-founded with Dillon Delvo in 1999 to save the area’s buildings and history. Based on a short story by Bulosan, The Romance of Magno Rubio recounts the pen pal courtship of Magno, an illiterate, immigrant farmworker, and Clarabelle, a white woman from Arkansas. The romantic correspondence is maintained by Nick, a more educated manong (and stand-in for Bulosan). While the promise and fantasy of the courtship is central to the plot, the play also stages the everyday experiences of these manongs – as immigrants, laborers, and young men.This past June 4, 2020, Lucy San Pablo Burns (UCLA) and I collaborated with the New York-based Ma-Yi Theatre Company to co-present a livestream screening of The Romance of Magno Rubio followed by a Q&A with actors Ron Domingo, Jojo Gonzalez, Ramon De Ocampo and dramaturge Professor Joi Barrios (UC Berkeley). Aiming to bring awareness to Ma-Yi Theatre’s work, the event kicked off SEAP’s 70th anniversary year and celebrated the inaugural Pilipino Studies minor at UCLA. At the heart of the event was our Manang Dawn – a UCLA alumna, a historian of Filipina/o farmworkers, and the daughter, niece, cousin, kumare (friend) raised by the manongs and manangs of California. Taking place amidst the events unfolding after George Floyd’s death, our live-streaming event and Q&A took on extra meaning as it underscored the dehumanizing effects of racism throughout America’s history while it also recalled the radical tradition of Philippine theatre and its making.

Flyer for June 4th The Romance of Magno Rubio live-streaming and post-screening Q&A

Its script composed of rhyming couplets, Magno Rubio centers Filipino performance forms and traditions – including the kundiman (romantic song), eskrima (Filipino martial arts), and balagtasan (verbal jousts) – as it tells a story of love and debt – love for a romantic other and for a home left behind, debt circumscribed by money and structuring sociality (i.e. utang ng loob or indebtedness to another person). In addition, as Joi Barrios points out, Magno Rubio “construct(s) characters reminiscent of the drama simboliko (symbolic drama)” – a theatre form that articulated the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist sentiments of the Filipino during the American occupation at the turn of the 20th century.” Here, we recognize the play’s “affirmation of the nationalist project in the Philippines.”When viewed within a longer Philippine radical tradition of theatre, including the early 20th century Philippine seditious plays produced under U.S. colonial rule, we also begin to see Magno’s relationship to Clarabelle as an allegory for the Philippines’ relationship to the U.S., one maintained by the promises and fantasies of reciprocity, futurity, indebtedness. By choosing to center Filipino theatrical traditions in this off-Broadway production, Ma-Yi envisioned a diverse audience that would recognize these performance forms, their histories and politics. At the same time, the show decolonized how Filipino stories, especially those in the diaspora, are told. By telling a Filipino story utilizing the techniques and styles of Filipino culture, Ma-Yi’s Magno Rubio works to undo any notions of a Filipina/o without a culture or history of her own.

Founded in 1989 by Chito Jao Garces, Ralph Peña, Margot Lloren, Ankie Frilles, Luz de Leon, Isolda Oca, Arianne Recto, Cristina Sison, and Bernie Villanueva, Ma-Yi Theatre Company also benefited, in its early days, from the involvement of Chris Millado as advisor to their first performance as well as playwright and director on future productions. An award-winning theatre organization that has developed new work by Asian American writers for the past 31 years, Ma-Yi is clearly grounded in the New York theatre scene. Yet, at the same time, it does not forget its founders’ earlier involvement with Peryante (formerly University of the Philippines’ Tropang Bodabil or UP Vaudeville Troupe) “a street theater group active from 1980-1987, a period of the Marcos dictatorship and Martial Law (1972-1986).” Thus, as Barrios writes in her introductory essay to Savage Stage: Plays by Ma-Yi Theater Company, “whatever the circumstances that prompted us to go to the U.S. … we brought with us to the site of migration Nicanor Tiongson’s definition of Philippine theater (“repleksyon ng pangangailangan ng nakaraming Pilipino” or “a reflection of the needs and aspirations of the greater majority of the Filipino people”) and the ideology of the ‘politicized artists’ of the Philippines.”

Armed with this ideology, Ma-Yi has expanded its scope, helping to develop and produce plays by, for, and about Asian Americans, while still maintaining the connections between U.S. and Philippines-based artists, actors, and playwrights. The version of Magno Rubio, which screened during the June 4th event, is a testament to such connections and transnational commitments. Filmed in July 2003 by New York-based filmmaker Francisco Aliwalas, this performance took place at the Cultural Center of the Philippines in Manila before a live audience and as part of the Sangandaan Festival. Peña and Ma-Yi decided to share the recorded production via live-stream from May 25 until June 4, during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic’s shutdown of theatres. This digital turn was just the beginning for the company who has gone on to share other filmed performances and, most recently, developed its own Ma-Yi Studios, a broadcast studio for short films, live broadcasts of plays, readings, music performances, to name a few.

While Lucy and I did expect a good turn-out for this event – as it brought together faculty, staff, students, and community members from three Southeast Asian Studies-networked universities as well as four distinct geographical areas (New York/the Northeast, Southern California, Northern California/Bay Area, and the Philippines) – we were deeply moved by the deep artistic, political and personal attachments audience members had to the play. While we thought the story of Magno Rubio would resonate with Filipino immigrants and their children, the aesthetics of the show with scholars and students of Filipino arts and culture, what we did not anticipate were the ways in which the digital turn would greatly widen the audience for Ma-Yi Theatre’s important work. No longer impeded by air travel to New York City or Manila, more people across the country and the globe were able to experience firsthand this play’s artistry and storytelling. The ways in which this took shape are best reflected in the comments provided by audience members during the post-panel/Q&A discussion.

As Lily Ann Villaraza, professor and chair of the Philippine Studies department at City College of San Francisco, noted:

“(That’s) what really struck me about this piece – the lyricism and poetic structure of the narrative. It really did remind me of Philippine theatre and Philippine literature in general. The way that the audience was drawn in as another actor to the play too. It took my breath away. As much as the story is grounded here in the U.S., it felt very much like a theatre production you would see in the Philippines. But then again, I should not be surprised given the talent behind the story.”

Through the play’s bare staging and barbed wire perimeter – a design choice that creates a relationship and relationality between the audience and actors – Magno Rubio was able to draw audiences into the action and feeling of the play. Through the rhythm of speech and movement of the play itself as performed by the barkada (tight group) of actors, through the lilting of their voices and tempo of their conversations, we were drawn into the everyday lives of these young men, who are often only seen in photographs or in their present older age.

In spite of U.S. capitalism’s dehumanizing effects and the romance of community, the manongs of Magno Rubio are young, vibrant, and three-dimensional characters. We are drawn into their world: their disappointment with dreams deferred and exhaustion with America’s broken promises. We are drawn into their inter-group dramas and internal conflicts, into what Joi called their “makisama” or practices of being together (ones that Lucy pointed out as a particular “complex migrant homosociality”).

Another important segment of the audience that evening were the families of actual manongs. As Glenn Aquino reminded us that evening:

“I’m the son and grandson of Filipino farmworkers in central valley California and I think it’s important to remind folks that there are still Filipinos working in the agricultural fields of California and canneries in Alaska. I know this because many of them are my relatives and that this story is still as relevant as ever. Thank you for bringing this back.”

With this, we are reminded that the figure of the Filipino farmworker in America is not just one of the past but instead an integral part of today’s migrant/laborer struggle.

If we think of farmworkers as part of America’s present, then we must shift our understanding of the Filipino’s relationship to migration, agriculture, and labor as one not simply of the past, but also of the present. How might we, in turn, unite the Filipino farmworker’s struggle in the U.S. to that of farmworkers in the Philippines who are currently being killed at high rates, as Joi pointed out during the Q&A? How might we understand that the forms and practices of dehumanization that Magno Rubio underscores are not just relegated to a long-ago past but speak to our global present?

Magno Rubio cast members visit a recreated bunkhouse with materials found in manongs’ trunks in the Daguhoy Lodge of the Legionarios del Trabajo, one of the oldest Filipino American fraternal lodges in the U.S.

Finally, as an event organized by and featuring scholars from Cornell, UCLA, and UC Berkeley, the event’s audience was, as expected, composed of students from these campuses’ Filipino American studies, Asian American studies, and performing/media arts classes. With this in mind, the final question came from UC Berkeley student, Vince Marie Cuison, who asked the panelists if they had any advice for young, aspiring Filipino writers, artists, and performers. Vince’s questions were preceded by her heartfelt admission that our communal viewing of Magno Rubio, as a play & event that centered Filipino histories, culture, and artistic forms, deeply impacted her as a student and emerging artist.

As scholars, we often forget the impact that viewing high-caliber productions such as Magno Rubio can have on our students, especially those inclined toward the performing arts. To understand that one can draw from one’s own cultural and artistic traditions, to see the possibility of Filipino actors onstage and on-screen playing three-dimensional (i.e. not stereotypical) characters, to begin to imagine how to write and stage a world based upon one’s own history, and to do all of these things in an unapologetic and decolonized fashion. To do so is to work in the spirit and manner of our Manang Dawn Bohulano Mabalon.Rather than simply assimilating, in what ways can we as artists, scholars, students bring our cultures and histories to bear upon American institutions – be they of labor/farm work, American theatre, or even the university? What might this work especially mean for us, the children and grandchildren of former U.S. colonial subjects? How might we as the offspring of immigrants, or as immigrants ourselves, continue in the decolonial tradition – centering and valuing Filipino cultures, histories, organizations and their study?

This is the work of Ma-Yi Theatre and its artists. This is the work of UCLA’s Pilipino Studies minor and the future of the Southeast Asia Program (SEAP) at Cornell. This is the work of students, scholars, and community members as we continue to advance Filipino studies, Filipino lives, and Filipino futures in the U.S., Philippines, and beyond.Magno Rubio cast members & Little Manila Board members (from left: Dillon Delvo, Paolo Montalban, Lailani Chan, Ramon de Ocampo, Jojo Gonzalez, Art Acuña, Jeannie Barroga, Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, Joseph Anthony Foronda, Elena Mangahas)