Migrations Program

Faculty Research Seed Grants: Global Hubs Info Session

September 18, 2025

12:00 pm

Join this info session to learn about 2026 Global Hubs Faculty Research Seed Grants offered by Global Cornell as part of our Global Hubs initiative. Info session attendees will learn about the grant opportunity and application tips through a short presentation and Q&A.

Through these seed grants, Cornell faculty from across the university are invited to apply for research funds to work with collaborators at Hubs partner institutions. Funded projects should lead to tangible outcomes, including the submission of at least one co-authored peer-reviewed publication and at least one application for external grant funding.

Up to 20 applications for research with a Global Hubs collaborator will be funded.

Successful proposals will receive up to $5,000 from Cornell, with the potential for matching funds from some Global Hubs partner universities.

Application deadline: October 15, 2025, 4:00 p.m. ET

Project duration: January 1–December 31, 2026

Virtual information sessions:

September 18, 2025, 12:00–1:00 p.m. ET (register)

October 1, 2025, 12:00–1:00 p.m. ET (register)

Learn more and apply for a Global Hubs joint seed grant.

Additional Information

Program

Einaudi Center for International Studies

Latin American and Caribbean Studies

Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies

East Asia Program

Southeast Asia Program

Institute for African Development

Institute for European Studies

South Asia Program

Migrations Program

Southwest Asia and North Africa Program

Bird Lovers to Flock to Cornell for Migration Celebration

Families, birders, and nature fans will descend on Sapsucker Woods this Saturday for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s biggest event of the year: Migration Celebration 2025.

Additional Information

18 Cornellians Receive Fulbright Awards

With Support from Einaudi

They will conduct research, study, and teach English in Canada, France, Honduras, India, Jamaica, the Netherlands, Norway, and Taiwan.

Most will be on site by October.

The Fulbright program is the U.S. government's flagship international educational exchange program. The Einaudi Center administers the Fulbright program at Cornell, providing all the resources students and alumni need to apply for Fulbright funding for international experiences.

Cornell consistently ranks as a “top producer” among universities with the highest number of candidates selected for the Fulbright U.S. Student Program. With this year's Fulbrighters, we are celebrating over 600 awards since the 1940s!

We're excited to congratulate conservationist Kyrin Pollock, one of this year's five Fulbright–National Geographic Award recipients—and the first Cornellian ever to receive the prestigious award. Kyrin will spend the year working with the Olokhaktomiut Hunters and Trappers Committee in Ulukhaktok, Canada, to document how industrial noise is transforming Arctic waters. Watch for more news about her journey from National Geographic and Einaudi.

The next cycle of Fulbright U.S. Student Program is open now. The Einaudi Center encourages Cornell undergraduate students, graduate students, and recent alumni to explore the opportunity and apply.

Meet the Fulbrighters

Alexis Anderson '23

Honduras

Research: Impacts of Coastal Pollution on Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease in Roatán, Honduras

“Improving the knowledge base on how SCTLD spreads is critical to help stop further global expansion of the disease.”

Erin Connolly '22

Norway

Research: Phorid Fly Biodiversity Across the Latitudinal Gradient of Norway

“Early months of my work in Trondheim will be based in the laboratory …, while the later months of the award will be dedicated to … a diurnal sampling scheme fieldwork project.”

Isabella Culotta '22

Netherlands

Master of Design: Probing Our Perceptions of Waste at the Design Academy of Eindhoven

“Our aversion to speaking and even thinking about our waste constrains our discovery and implementation of innovative waste management systems.”

Gabriel Godines '23

Taiwan

English Teaching Assistant

“My experience in the U.S. Navy sparked my interest in East Asia, particularly in fostering understanding between the U.S. and China.”

Tenzin Kunsang '25

India

Research: Reconceptualizing Education in Exile: Transnationalism in the Tibetan Children's Village

“These findings will help … to promote domestic language and cultural preservation among Tibetan-American students amid the politicization of schools in Tibet.”

Michelle Lee '25

France

English Teaching Assistant

“Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, I missed an opportunity to study abroad in France. This setback has motivated me to regain the chance to experience the country firsthand.”

Tiffany Liu '22

Taiwan

English Teaching Assistant

“I … hope to observe the various technological initiatives currently pioneered by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan, including the movement to integrate AI.”

Kyrin Pollock, MEng '19

Fulbright–National Geographic Award Recipient (Canada)

Research: Arctic Echoes: Exploring Inuvialuit Knowledge and Marine Soundscapes in Conservation

“My work will address a gap in Arctic marine bioacoustics research … with documentation of Indigenous knowledge and an audio sample of the changing Arctic Ocean soundscape.”

Caitlyn Sams '25

Jamaica

Research: Herbal Medicine in Oncology: Safety of Psilocybin and Cancer Therapy Co-Medication

“This project will … spark conversations about herbal medicine use and promote avenues for holistic cancer care.”

Miguel Soto Tapia '20

Taiwan

English Teaching Assistant

“I want to undertake an English teaching assistantship in Taiwan because I love language, teaching, and mentoring.”

Apply for Fulbright

The Einaudi Center supports you throughout the entire process of applying. The Fulbright U.S. Student Program is open to undergraduate students, graduate students, and recent Cornell alumni.

Additional Information

Announcing the Winners of the 2021 Migrations Creative Competition

With their words and images, our 2021 creative writing and art competition winners answered the question: How does migration shape life in your community?

Table of Contents

- On Borders: Life, Deportations, and Mobilities along the Haitian-Dominican Border

- Sabor a Carne

- The History of Those Before Me

- Meridian Root

- Lupita's Shoes

- Water Diaries

On Borders: Life, Deportations, and Mobilities along the Haitian-Dominican Border

Karina Edouard, PhD Student, Anthropology

These photos were taken in the border town of Anse-à-Pitre, Haiti in 2017. At the time, I was working for the International Organization for Migration where I conducted research and collected data on the illegal deportation of stateless Dominicans of Haitian descent by the Dominican government. I spent a great deal of my time at various official border crossing points between Haiti and the Dominican Republic and witnessed the complexity of life at the border. There were innumerable deportations, as well as food stands, vendors, and transportation services. The Haitian-Dominican border reflects a space where tragedy and ingenuity, protest and resilience, and pain and joy seemingly converge. It is a space where mobilities are exercised both voluntarily and involuntarily, and where the Haitian state, the Dominican state, and the international aid community meet. Given this complexity, there can be no singular representation of the Haitian-Dominican borderlands. As such, I have selected seven photos I took during my time along the border that begin to give voice to this dynamism.

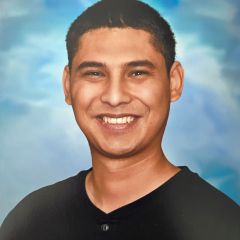

Sabor a Carne

Sabrina Haertig Gonzalez '22, Fine Arts

"And when did you first taste yourself in the Boneless Skinless Chicken Thighs Family Pack? *Freshness guaranteed*."

Sabor a Carne is a sculpture series navigating the relationship of Latinx identity to poultry processing in the United States.

These works represent dedicated, intensive research of how the Latinx body is taxed through forced migration, dangerous labor, and the consumption of American chicken. At the intersection of exploitative policy and culture, one can observe a phenomenon of cannibalism. Chicken, or pollo, an inseparable staple to Latinx cuisine for most, is also inseparable from the unethical modes at which it is farmed and processed in mass- which heavily exploit the Latinx community. The exploitation of migrant labor and systematic disenfranchisement of the Latinx community lead many to work in dangerous employment such as meat processing, which compounded with the economic accessibility and cultural relevancy of chicken, positions them as products, producers, and consumers.

As one assumes these roles, what becomes of the “self?” What becomes of their relationship to the corporeal? Do corporeal bodies blur as violence is imparted by the human and non-human? This discourse is presented to the audience through the surreal manipulation of the corporeal and industrial. From adopting pre-Columbian aesthetics to designing imagined future architectures, Sabor a Carne posits when meat became flesh.

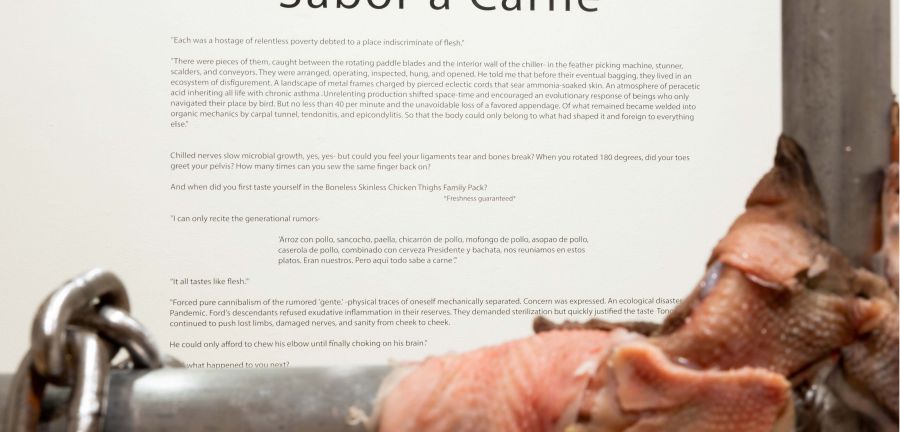

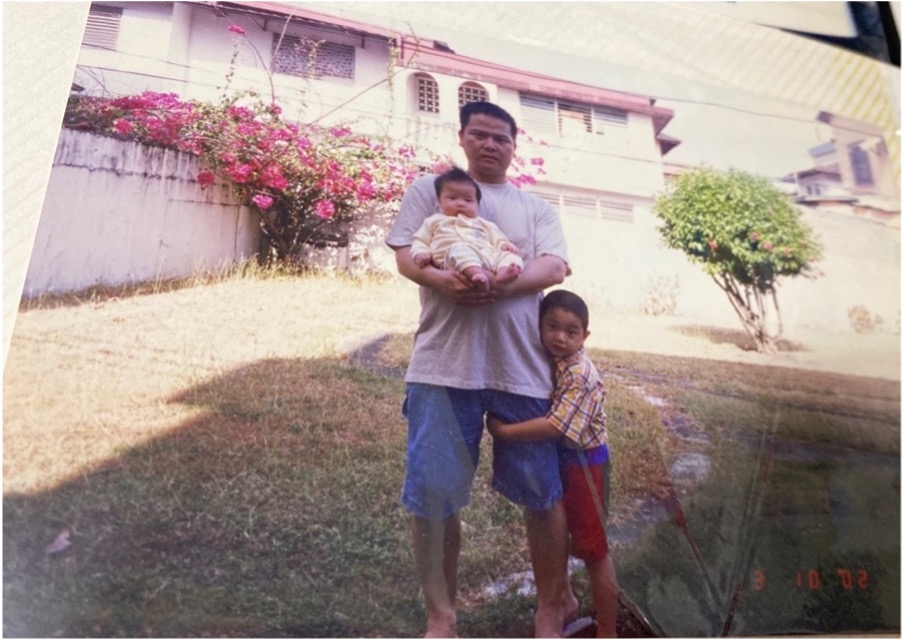

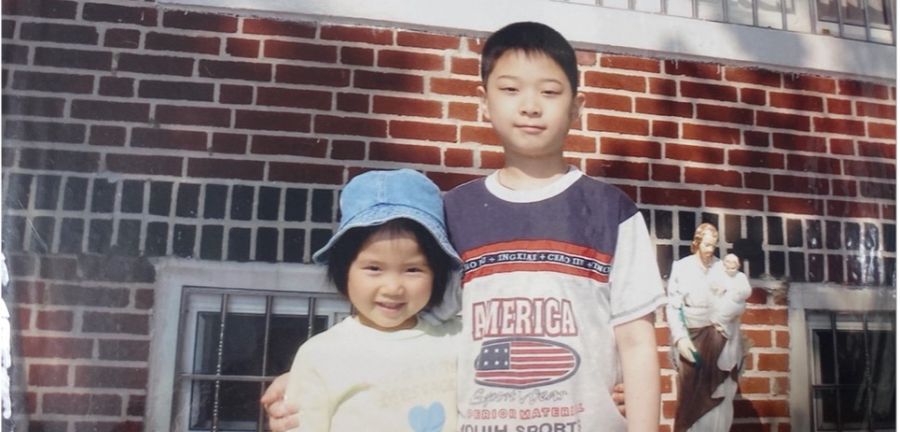

The History of Those Before Me

Michelle Cheung-Zheng '23, Environment & Sustainability

The education of the world beyond the urban landscape that raised me has been defined by the realities of the people and histories that brought me to my current community. In the re-education of my diaspora and family’s migration, "returning" became a concept that reconnected me to generations of land, families, and complex social networks. My perception of my family’s migration stories is weaved and shaped by the dispossession of identity, land, history, language, and culture.

My curiosity with my family’s migration history stems from the psychological dissonance between my identity and the cultural environment I grew up in. In New York City, where 11.8 percent of people identity as Asian American, internalizing experiences of discrimination and stereotypes became a subconscious reaction to processing my self-identity. Reconciling the dual identities that I felt as an Asian American woman meant that I had to understand more than my own upbringing; I had to understand the generational migration that happened within my family and how that impacted their relationships with the idea of home and what home represents.

The first migration story of my family I learned, entailing the weight of generational adaptation, starts in southern China. My father comes from a family of eight, the only son out of six children. Migration came out of necessity and a need for financial survival. Disinheriting land and property became an unspoken agreement, a necessary process that moved my father to a new country. Conversations of this dispossession revived when I went back to that house in 2018. Standing in its now empty layout, I imagined stories of his family, their home, and their departure from it.

About one generation ago, my father and his siblings moved to Panama where they continued to live for multiple decades. However, a new migration story ensues after I was born. My father continued to live in Panama for a few years while my mom moved my older brother and I to our new home in Brooklyn. How do we grieve for the lives we would have lived and the people we would have become? To reconcile this is to first acknowledge that my self-identity has been context-dependent on my family’s migration history.

The migration stories above only cover what has been disclosed to me and within the bounds of my immediate family. However, migration within the rest of my extended family represent stories of their own and will become networked into their own families. Different family members have chosen to stay in China, Panama, and the U.S. Some have migrated to other places. Migration chains and effects are extensive and represent different needs, geographically and culturally.

In some ways, I have repossessed pieces of identity through navigating my family’s history of migration. Each generation of my family is linked by the resilience of self-preservation in the environments that built our identities and lives in China, Panama, and the U.S. Cultural and social ecosystems are integral to how our identities become tied to land. Preserving my heritage means to preserve my relationship with developing my own concept of home, merging multiple environmental perspectives together.

I have many more questions about the emotional and psychological impact of migration on my family’s individual identities. However, understanding that migration is not a linear story and that many stories get lost, either in translation or intentionally left out, has impacted how I continue to access these stories from my family. Reconceiving notions of identity throughout generational migration is a continual process, one that requires mental acceptance to truly reconcile how migration changes your family’s history and ultimately, your own history.

Meridian Root

Nicholas French '23, Human Ecology

The scent of asphalt simmered through my nostrils as we stepped out of the AMC theater. The image of neon from the Algiers Hotel and gun smoke were burned into my skull. I could see my grandmother materialize, piece by piece, as my eyes acclimated to the bright summer sun. First the wispy curls of her hair. Then her skin. Finally, her eyes appeared. They were pensive, quietly shifting—caught in a current of memory. She was actively analyzing what we had both just witnessed, forming a solid critique with memory as her guide. I wanted to hear her thoughts. She became a link between the present and past.

"So what did you think about the movie, Grandma?" I asked.

Beneath her eyes formed a smile, a tentative smile suggesting satisfaction and the slightest hint of distaste.

"They did a good job, but they got a couple of things wrong," she replied. "Everyone burned down buildings in those riots. Not just Blacks."

My grandmother’s arrival to the North was not unlike the tales of many mid-century African American families migrating to northern cities.

To some, the migration north was a pursuit of economic opportunity—a movement from the Bible Belt to the Rust Belt. The automobile industry served as a catalyst for a growing midwestern middle class. To others, the move north embodied an escape from the terrorism of southern racism—an arrival to a new personal Canaan as segregation and violence still ran rampant in the South.

My grandmother’s migration north was motivated by many of these factors. However, above all, it was for the pursuit of a better life, for both herself and her new family. Her arrival was different from other migrants in one particular way—she came to Detroit during the aftermath of the 1967 Detroit race riots.

Mary Powell Wright began her life in Meridian, Mississippi. Though her family was not rich, they had what she fondly recounts as "a good life." Her father—my great-grandfather—was self-employed and one of the best auto mechanics from Alabama to the Georgia line. Car owners, both Black and White, brought their cars to his garage for repair. Their home was a haven of renewal, both for cars and their neighbors. My grandmother’s youth was dictated by the unspoken creed of Mississippi: "Feed your community, and the community will feed you." Whenever dinner was made, there was always extra for neighbors and whoever needed it. Yes, she was living the good life.

In college, she met a young man that she grew to love and, in the future, marry. However, the couple knew that they wanted to move North. The two made their decision to move in 1967. Equipped with a loving relationship and a desire for opportunity, the couple made their way to Detroit, MI.

With incredible luck, my grandma did not arrive to burning buildings and gunshots tearing through the skies. She caught the tail end of the uprising, witnessing the carnage only through the echoes of gunfire and the smoke of businesses reduced to ashes. To my grandmother, the rebellion was not a blaze of fire, but the sickening warmth of cinders and police posted in the distance. She witnessed what happened both through her eyes and the headlines of newspapers, frantically explaining what had occurred. A single false gunshot from the Algiers Hotel coupled with decades of systemic oppression created a whirlwind of rage and fury, burning much of the city to the ground. It was believed that many white storeowners burned down their own properties and were reimbursed through insurance. To them, the flames presented an opportunity to move their business out of a city growing more Black by the year. The flames and tanks threatened to consume the lives of the Black migrants. However, if there is one thing that they knew best, it was how to root themselves into the ground and sprout community—even if the soil was charred. She earned her degree in education and raised a beautiful family.

After living on Garland Street near the east side of the city, my grandmother relocated to the Black and Jewish neighborhood on Pinehurst Street, closer to the west side. As time passed, the neighborhood grew more homogenous as white flight and suburbanization further segregated the city. It was here that my mother, aunt, and uncle spent their childhoods, and would eventually create my generation. When her children came of age and went to college, she moved to the suburban city of Southfield, MI. There, I would spend much of my childhood alongside grandchildren of countless other southern migrants.

Southfield is a city of many identities. A city of rolling hills and tall weeping willows, populating the streets with the staccato chirps of cardinals and grasshoppers. This natural melody scored my childhood adventures, bolstering my courage as I first learned how to climb the massive tree in my grandmother’s front yard and jump on a trampoline without breaking my spine. It is also a city of communal empowerment—a trait inherited from the culture of the South. Each Sunday morning an exodus of cars could be seen flying from the neighborhood at 9:40 a.m. (on the dot), just in time for Hope United Methodist Church’s 10:00 service. Most of all, however, it is a city of hope and sacrifice. The sacrifice of comfort for future opportunity. The sacrifice of familiarity for family. The sacrifices that enabled me to live the life that I live today. My history is entwined with my grandmother’s—rooted in Mississippi culture, faith, and perseverance. Despite the uncertainty, smoke, and cinders—we are here. Migration is my story.

Listen to French's interview with his grandmother.

Lupita's Shoes

Amalia Schneider '24, Industrial and Labor Relations

Guadalupe’s day begins every morning at 6 a.m. She sits up slowly and stretches because her muscles are still sore from the day before. When she stands up wearily and makes her way over to the bathroom to say her prayers in the mirror.

When she was a girl her mother used to brush her hair and recite them with her. She continued this practice with her daughters, Sarah y Graciela, back when they all were still together in México. Without them there, ella le pide a Dios que reúna a su familia every morning while she got ready for work. She steps out at 8 o’clock to walk three blocks to catch the subway. The El train arrives 5 minutes late and floods with people as it rolls in at 8:32. Whenever she rides the busy train in the morning, she liked to observe the "strange people"—or strangers, as her English teacher had called them. This morning, she sat across from a mother with her young daughter having a conversation about "crayons" she doesn’t understand, but she writes the word in her little blue notebook to look it up. Once she reaches 69th street station, she is so anxious about being late she races to her next bus which doesn’t arrive until 8:55. When the bus finally stops outside the Apple store in "Suburban Square" she is clutching her android as it reads 9:15.

But, she quickly turns the corner and arrives.

"Besito."

From the sidewalk, you can already hear "El Beeper" by Oro Solido blasting out the walls. Manager Mike is already at the host stand typing on an iPad as she walks in.

"Damnnn chica, you're late again today? What are we gonna do with you?" Mike jabs sarcastically. She doesn’t understand, but she sees him start laughing so she does the same. She giggles awkwardly and says "I sorry" as she makes her way toward the kitchen.

She is so tired of laughing at Mike’s pinches jokes, especially since he hadn’t paid her for a single shift all week. Of course Carla the bartender is always there with a flower pinned in her hair and a full face of makeup at opening to greet Guadalupe.

"Hola, mi amor. ¿Cómo 'stas hoy?" she exchanges in her beautiful Venezuelan accent.

"Bien," she says as Carla blows her a kiss that she steals with her into the kitchen. She sets her purse under the metal rack of plates and ties on her apron that still smells of salsa from the day before. Hours go by as she squats at a 90-degree angle to lift the 3 foot, 8 pound black trays that carry the food.

Le duele el cuerpo.

She looks down at her tattered black shoes. The soles of her work shoes have become indented from the hours of intense lifting; it’s at the point where wearing them for more than an hour makes her hip and spine ache, but she can’t afford to think about buying a new pair until they pay her. After the fifth hour on her feet, she starts to feel dizzy and asks manager Mike if she can take her afternoon break. As the break room gradually fills with more of the servers for the night shift, the bilingual chatter soars until the 7 o’clock news silences the chatter. "These people are criminals, drug dealers, murderers, rapists," he says.

¿Criminal?

The word played in her head while brushing her hair that morning.

It made her question herself.

Was it criminal to want a better life? Criminal to cross an imaginary line when you have no other option? Or is it only criminal when you have brown skin and a thick accent?

"They're stealing American jobs!"

That one made a server LaLu burst out chuckling. "¡Aye you can keep your pinche jobs, orange man! Besides, ain’t nooo ICE gonna catch me," and he lightens the mood by jogging with high knees.

Amidst the laughter, I come in for the start of my shift with Guadalupe. She launches from her chair and hugs me. "¡Hola, cariña! ¿How are ju?" she asks me, grinning.

"I’m good," I smile back.

"I have uhh-a-soorpriseh for ju." She reaches in her purse and pulls out a plastic container with a slice of carrot cake.

"Aww, Guadalupe, What is this for?"

"¡It is for ju!"

"But why?"

"Because ju got accepted in de university and I..." She wrinkles her nose in thought and then closes her mouth tight. She squeezes my shoulder gently as if to signal what she had wanted to say got lost in translation.

"Thank you," I said. "We can share it."

"¿Sharar?" She looked confused.

"Compartir,” I translated, and she nodded and smiled.

This was the last time we were all together as a family at Besito before COVID scattered each of us back to our own corners of Philadelphia. IfI had known that was the last time I would see Guadalupe, I would’ve made sure that I never lost contact with the woman who had become my family through work. Even though she was 65 to my 17, I could do nothing but empathize with this kind woman who gave up everything in migrating—respect, family, stability—and worked nonstop to help those she loved in Mexico. Through Guadalupe especially, I watched all the ways this country makes immigrants feel invisible, yet burdensome at the same time.

So, while writing this story cannot undo all the injustice Guadalupe has received for something as human as migration, at least I can find some peace in knowing that she is no longer invisible here.

I write this to rebuke on her behalf the notion that immigrants deserve anything other than empathy. "Illegal" or not, immigrants are still people—people who shouldn’t have to beg and plead for understanding. Dios sabe que they’ve been through enough. So, I invite you to take a walk in Lupita’s shoes.

Water Diaries

Skylar Xu '24, Comparative Literature

When we first moved from home-town to big-town, grandma couldn’t get used to the water. She would filter the tap water using a row of large pitchers and jars, letting water sit before passing it to the next pitcher or jar. Grandma had lived most of her life in home-town. The water there was different, she said. Softer. You could feel it on your skin when you showered. The water was softer. What she means is that the water is less alkaline. Anyway, it was years before we got a water filter installed beneath our sink, so she filtered water with a row of pitchers and jars. I grew up drinking kettle-boiled water.

(Is there something in the water?)

There is a difference in taste between boiled tap water and bottled water. I know this because I grew up in a country where tap water was not potable. Boiled tap water has a cloudy, vague texture and usually doesn’t taste like anything. Bottled water, on the other hand, is sweet and bitter at the same time, leaving a dry sensation like the aftertaste of a too-green banana or that of an early persimmon on your tongue. I never got used to the taste of bottled water. I’ve lived most of my life in big-town. It’s called big-town because it’s bigger than home-town, and because it’s where people go if they want to make it big. Whenever we visit home-town, I try my best to gauge the softness of water like grandma had described. If I did feel it, chances are I imagined it or it was some sort of placebo effect. But I was born in home-town, and since it was where my parents and grandparents lived for most of their lives, I always wanted to feel like I came from home-town, too.

(Is there something in the water?)

People from home-town say I sound like I come from big-town, and people from big-town say I sound like I come from big-country when I speak the language. I have never heard anyone other than myself talk about the smells and tastes of water. Maybe I’m crazy. I might as well be, because now I’ve left big-town, more or less on account of my own will, if you can call it that. I’ve quit home-country for big-country. And here in big-country, they drink tap water.

(Is there something in the water?)

I was fifteen when I first came to big-country. I was fifteen, so I don’t think it was a decision based purely on my own will. I didn’t even know why it was called big-country, only that everyone else had called it that. When I first came, I couldn’t tell if the water was softer or harder, only that alkaline formed on the base of the electric kettle. When I was really young, water was boiled in a kettle that was not electric. It sat on top of the stove and whistled when the water was ready. A shrill but not unsettling whistle.When my parents were my age, they lived in home-town. They must have gotten a taste of big-town water one day, because all of a sudden soft home-town water wasn’t enough for them anymore. They had to move to big-town, as if there was something in the big-town water. I wonder if the same thing is in big-country water, too, because after a taste of it, home-country water wasn’t enough for me anymore.

(Is there something in the water?)

A water filter gets put under the sink back home, in big-town. The new filter is supposed to make tap water potable, but no one uses it. We’re used to drinking boiled water. Tap water, filtered and drinkable, still feels like tap water. I bet it’ll even still smell like tap water. Ever so slightly metallic and reminiscent of clean soil. Here in big-country, no one can tell that I’m from home-country by the way I talk. In fact, I don’t want anyone to tell that I am from home-country. When I speak in class, however, my voice tastes like tap water. Undrinkable, slightly metallic, reminiscent of soil. But this time it’s the kind of raw soil that dirties your hands, not the clean kind that nourishes gardens. I imagine myself taking on stutters, starchiness, and a raspy quality that my voice does not have. No one else hears them but me. Everyone else’s voices taste like bottled water. In home-country, tap water is becoming potable in some places. We have electric kettles now, and we only use the shrieking kettle when the power goes out. Big-town water still won’t be as soft as home-town water, though, and I know neither of them will really be the same as the water in big-country. Is there something in the water?

Additional Information

Program

Announcing the Winners of the 2022 Migrations Creative Competition

How does migration shape life in your community?

Table of Contents

- Zungueira Mundial

- Creating Home

- Reluctant Fundamentalists During Seasons of Migration to the North

- The Migration of a Daughter to Immigrants

- Weaving: Spring 2021

- Who Knows the Arbitrariness of Being Born Some Place and Its Significance

Zungueira Mundial

Cátia Dombaxe, PhD Student, Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering

I was born in Luanda, Angola, in a culture where the philosophy of Ubuntu has such a deep personal meaning that it felt like this life philosophy was engraved in me from a young age. Growing up, I really did not understand individuality, because I was always part of the collective. I was part of everyone, and everyone was part of me… That is how I grew up and to this date I hold true to these beautiful roots. UBUNTU, one of my favorite life philosophies, will always define who I am and allow me to strive for and achieve ever-increasing challenges that I undertake.

The concept of Ubuntu has been developed by Desmond Tutu, but many Bantu tribes in Africa have lived by the principles since the early years. Ubuntu is a way of living; Ubuntu means I am who I am because of all of us. Ubuntu is part of the collectivism I spoke above. I live by it and I would highly advise you to adopt it and make it part of who you are. Ubuntu has shaped me and allowed me to grow because of the infinite support, life lessons, and a sense of belonging.

Ubuntu has allowed me to adapt in every environment I move into and make that my home as well. Ubuntu to me is migration, migration is zungueira mundial, and zungueira mundial is all of us.

Zungueira mundial is Portuguese. In Angola, a zungueira is a slang term for a peddler woman. It is a woman carrying a large plastic bowl of food and many other goods on her head, with a baby strapped to her back, trying to survive Angola’s difficult economic challenges. Zungueiras are very well known in Angola, due in part to their tenacity and willingness to do what it takes. They are known to walk great distances in order to sell their goods and make money to feed their children.

I associate with zungueiras because migration is survival for me. I, too, have walked great distances to get where I am, carrying the weight of the people and places I have met and explored, because I feel I carried the responsibility to connect them to you. For me, this is how I feed not only myself but also the world.

With these photographs, taken around the world during the different migrations of my life, I truly would like to entice you to look beyond visuals. I want you to feel it: every place, every face, every smile, please feel it! That is migration. I urge you to explore, get out there, meet people with different backgrounds, each and every one tells a story, learn something with them and something about yourself along the way.

Explore beyond your roots.

Click on the image above to see the complete photo gallery.

Creating Home

Ishika Agrawal '23, Information Science

The following set of poems are written from three different perspectives—a grandmother, a mother, and a daughter. It explores the intergenerational relationships that immigrants retain with their homeland and its histories pre-migration, just after migration, and a generation later.

I. The British Raj

seven letters weigh 89 years of dreams deferred

of don’t worry, I’ll walk

the 5 rupee bus pass costs too much

of here, this is how you chop

a knife, not a scalpel, fits a woman’s palms

of please, say your grievances

my 8-month-old brother was just killed by an officer with a rock

August 1947

after 89 years of ice

pots clang

hoisted at full mast

a flag torn into three parts

it’s time now -

to fulfill every deferred dream still hovering

the family tree path

do I have what it takes?

that matters not

it is a duty I carry

passed down to every child,

keeping our ancestors alive

with the same seven letter family name

II. Time Capsule

I massage almond oil into my hair

just as my mama did

sip my chai from a red clay cup

just as my papa did

choose a matching bindi every morning

just as my nani did

sing the Gaytri Mantra head bowed to Lord Ram

just as my dadu did

8000 miles away

I’ve created a piece of home

that smells like ground clove and rose agarbatti

sounds like the chattering of aunties as they knit woolen scarves, away from the monsoon rains

feels like the early morning excitement just before the whole neighborhood arrives to play Holi

but as I’ve built my home

scouring my memories

to put it together piece by piece

the world has changed

8000 miles back home

my niece prefers an organic rosemary hair serum

to my mama’s almond oil

my brother-in-law prefers a ceramic mug

to my papa’s red clay cup

my sister prefers the modern look

to my nani’s bindi

my nephew prefers Coldplay

to my dadu’s early morning aarti

the home I long for 8000 miles away

isn’t truly home anymore -

my people have changed

my culture is dissolving

my world has moved on

but in this time capsule called home

that I’ve built

I can pretend.

Nothing

has changed.

III. Home

I imagined home as the

four lemon sorbet walls tucked between sugarcane fields.

Before that, it was every story my grandmother

told. It was sitting on marble floors

gulping alphonso mangoes, juice running from the mouth. It was

the I miss and the I wish and the Grandma,

there are no mango trees here.

It was a desert mirage, blurred

by a post-Diwali firework haze -

a distant, foreign familiarity

conjured by my mother’s peculiar love

of peacock feathers and fennel seed paste.

Spray-painting my bottle-green bedroom

with Benjamin Moore’s can of lemon sorbet.

I declare I am home.

Who needs sugarcane fields when living

the white picket fence dream? Who needs

alphonso mangoes when there’s plenty of apple trees?

Boarding the New York subway, my two-year old sister

rests her hand on a gentleman’s knee.

He brushes her imprint off, as if

swatting a flea. My father warms my dinner

as I read in the hotel lobby when a concierge’s

What is that smell? febreezes the aroma of palak paneer.

I gulp an apple but the seeds get stuck in my throat -

a sore reminder of why mangoes have juice and

picket fences can’t contain sugarcane fields.

Reluctant Fundamentalists During Seasons of Migration to the North

Shehryar Qazi '24, Government

The title of this piece refers to two novels: Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist and Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North. If I had to describe what the book was about, I’d say it's about hybridity and being a colonized subject in the imperial core. But my readings of the texts are fundamentally colored by the similarities I share with the characters as a colored, foreign man attending one of the most prestigious institutions of higher learning in the West. All our lives are so fundamentally shaped by migrations: labor, educational, and political. So fundamentally, I can’t disentangle my reading from my life, and the texts become about who the migrant really is, who I “really” am, especially divorced from any sort of “native” context.

Both texts are incredibly packed and dense, so I will note that there is so much more to them than some of the things I talk about. Seasons of Migration to the North is a sort of “Arabian Nights in Reverse.” The story follows the life of one Mustafa Sa’eed, a brilliant economist from Sudan who studies at Cambridge and becomes a respected anti-colonial economist among the highest ranks of British society who returns to Sudan to start anew, through the lens of a narrator who is also British-educated Sudanese and becomes obsessed with Sae’ed. The Reluctant Fundamentalist is about Changiz, a Princeton-educated Pakistani investment banker and his reaction to 9/11, eventually returning to Pakistan because of the racism he faces after 9/11 and getting a job at a university criticizing American intervention in Pakistan.

These two texts raise a lot of ethical questions about complicity and about self-authorship, and I consider them in lieu of my social milieu. The third world aspiring upper class educated in the West, with hopes and dreams of achieving status as part of the international leisure class. I more so think of this when I think of my Pakistani friends who break into the top computer science and finance firms in America, and my heart aches to know that some of the sharpest and most brilliant minds from home are using their abilities to exploit the Global South, servicing some of the most crooked and evil institutions of the world. But many of them do not have Changiz’s realization in The Reluctant Fundamentalist that the actions they are doing make them foot soldiers in American Capital’s destructive war on the rest of the world. Instead of Reluctant Fundamentalists, they remain eager janissaries.

But then again, the life of the scholar represented by Mustafa Sa’eed is not without its ethical problems either. What does it really mean to produce knowledge about the place you’re from, especially in the context of the Western Academia? The conversation about the centrality of indigenous dispossession to the project of the American university system is slowly rising in volume, but has yet to seriously explode to the point where we acknowledge and do the reparatory work necessary to deal with this legacy of dispossession. But there’s more to this, as the American academy and production of knowledge is so influential in how we view the world. From the creation of the atom bomb at a squash court at the University of Chicago, to the printing of Mujahadeen textbooks at the University of Nebraska Press, the American academy has been deeply involved in the twentieth century’s most destructive developments. “Knowing” always has political implications and if you’re in the position as a foreigner to contribute to this system of “knowing,” then you probably represent a very select, usually upper-class, social and cognitive group. The figure of the metropolitan migrant is a limited one, yet it is the best we can seem to do in the American academy.

But this is not to be wholly critical of everything ever produced out of the American university. This essay is produced out of this system. Nor do I have answers to the ethical problems confronted by the figures of Changiz and Mustafa Sa’eed. I simply wish to raise them and see where they lead me into thinking about what sort of life I want to live.

My family history has migration built into it. My grandmother from my dad’s side was from Iran and moved to Ferozpur, now in Indian Punjab, to marry my grandfather who had been a judge in the city for generations. They then moved to Gujranwala, in now Pakistani Punjab, during Partition, and then moved to Lahore in the early 1950s. My grandfather and grandmother took a world trip during the early 1970s, their trip to New York being recorded on home video. My mother’s family moved from Sialkot to Lahore and is now scattered all across the world, from America to the UK to Russia to Saudi Arabia.

I myself always knew that I would spend significant time outside Pakistan, but am challenged by this time outside. I have not been “home” in five years, and have somehow found myself in Cornell's government department, having to sit through abstracted discussions of drone strikes, knowing what they were doing to people in Pakistan in the 2010s. Terrorism became a form of “asymmetric warfare” and suicide bombings as “insurgent weapons,” and not the reality of living or growing up in Pakistan during the War on Terror. I always felt a sort of disconnect between my life in Pakistan and my educational life in America.

I read the two texts as cautionary fables. Of course, no one will ever fully be a Changiz or a Mustafa Sa’eed, but these two figures are warnings of life in the West for the Global Southern metropolitan migrant. But these two texts also firmly deal with the question of return, which is presented as a bittersweet situation. Depending on how you read the stories, both Changiz and Mustafa meet unenviable ends. But I can only sigh at my disconnect from “home,” unsure of return. Maybe that is an unenviable end in and of itself.

The Migration of a Daughter to Immigrants

Fatima Martinez '24, Psychology

If I were to mention the date March 13, 2020, you, me, and almost the entire world would remember that date as the day the world stopped. COVID had forced us all to isolate, drop our daily routines, responsibilities, and take them home with us. But that day, in particular, I remember it as the day my world stopped but also started. Does that make sense? I know it sounds crazy. But it was the day I was getting ready to leave school for “two weeks” when I received an email. Not thinking much, I opened it and received a likely letter from Cornell University. Given how crazy the day had been going, I had to reread the letter five times before I actually understood what I was reading. And then I felt my heart drop to my stomach.

“Is this real?” I asked my younger brother as I showed him the email I received on my phone. The rest is a blur, but I remember him crying, shouting at my face with excitement, shaking my shoulders and saying, “You got in.”

When I told my parents that I got into Cornell, they didn’t really understand. The only thing they processed was that it was a school in New York. “Why do you want to go to school in New York? I came to Los Angeles because it has everything. And now you’re leaving it!” said my dad.

“She wants to leave us. She wants to leave me,” said my mom.

My family didn’t understand, only my 15-year-old brother did. He was the one who convinced me to apply to Cornell in the first place. Regardless, I let the subject of conversation go because part of me felt like my family was right. What if the likely letter was actually sent to me by someone who was trying to play some joke? What if this was all a lie?

“No vas a ir. Ya te dije,” yelled my mom.

“Why not? Can’t you see this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity?” I responded.

“You just want to leave me. And leave all of us. Is that what you want, to abandon us?”

"I never said that! Why would you even say that?”

“Then why do you want to go?”

“Because they’re a good school. They’re paying everything!”

“There’s no need to go so far, not in the middle of a pandemic! And you know that just because they're covering tuition doesn’t mean there aren't other costs. What about your plane tickets? Essentials?”

“I’ll figure it out. I’ve saved up enough money from my summer jobs.”

“If you leave, I’m not helping you. I’m not going to drop you off.”

“That’s fine. I promise I won’t ask you for anything.”

At the end of this conversation, I was in tears, snot was coming down my face. But I was determined to go, I had worked so hard for exactly this. Maybe not particularly aiming for Cornell, but for a good school—to make it out.

By the end of the summer, I had shipped two boxes across the country and only had my father’s blessing. “Es por tu bien, yo entiendo,” (it’s for your own good, I understand) he said. “Yo también hice lo mismo, solo que yo no migre solo. Yo vine a este país con tu mama, casado y a los treinta años de edad. Tu mama tiene miedo por que tu estas haciendo lo mismo—pero estás viajando sola, a los diecisiete años y en medio de una pandemia.” I understood what my dad tried to tell me, but somehow I still felt hollow inside, so hollow that I could feel my heart in the pit of my stomach. My parents were and are the reason I do everything I can do in my power—my desperation to make it out was not for me, but for them. So that crossing over, leaving their family behind, and starting a new life with twenty dollars in their pocket would not be in vain. I had developed enough anger and grit all these years so that we would not spend another holiday fearing the police, the possibility of la migra deporting my parents, or having my parents work on holidays to make the extra money. How could they not see that I was doing this for them?

As I reflect back, I think about how the roles of us immigrant families reverse over time. Our parents are superheroes to us, machines who never stop working hard—even through the most painful times. But as I am older, I see my parents as individuals I must protect from the government and the world. And although they may not have understood how good of an opportunity Cornell was for me, I had to pack my bags and move across the country on my own.

This is where my story begins. And although part of me hasn’t really reflected on all of it, or my journey thus far, I plan on telling it and writing it. If there is one thing I remember from my freshman year, it’s my English professor telling me, “Lots of people love reading, listening to songs, and watching movies. But it’s because everyone has a story to tell and if we love it, it’s because the writer was able to express something that we were not able to do ourselves yet resonate with.”

For many generations, those who migrate always migrate to places that provide better opportunities and a lifestyle than the one they had before. This is why my parents moved here almost thirty years ago, this is why I came here two years ago, it’s why thousands of people risk their lives everyday just so that they could get a taste of a better life. So let me ask you, if you were miles away from living the life you wanted, wouldn’t you take that chance?

Weaving: Spring 2021

Maiko Sein '23, Architecture

On January 31, 2021, my world, my family’s world, my community’s world was turned upside down. On January 31, 2021, there was a military coup in Myanmar. On January 31, 2021, like the generations before theirs, the youth of Myanmar took to the streets and protested for freedom, democracy, and peace. On January 31, 2021, like the generations before them, the military junta aimed weapons at them. On January 31, 2021, around the world, from NYC to Tokyo, the Burmese diaspora community, many of whom were displaced by the same military, took to their own streets and protested for freedom, democracy, and peace. For many it was familiar as they had done the same in their own youth. On January 31, 2021, the children of the Burmese diaspora community joined in on the fight for freedom, democracy, and peace for their parents’ country, for their grandparents’ country, for their friends’ country, for their country.

This was the start of the Burmese Spring Revolution.

The work is a plaid weaving titled Spring 2021. The warp, the up and down, are the protests, memorials, and fundraisers that my family and I attended throughout the NYC and Tri-State area. They are organized by the Burmese diaspora community in the area. The weft, the side to side, are the moments that spring that kept me stable. They are of my family, of home, of Zoom school. Together they interweave to tell the story of my Spring Revolution.

As a Burmese-American, I felt I was living two different realities that spring. The first reality as a newly turned 21 year old navigating the post-pandemic world, scared for the future but also scared for my friends and family in Myanmar. The other reality, I was more than myself. As I stood with the Burmese community at protests and memorials, I had never felt more strong and empowered. A year later, through this collage, am I able to decompartmentalize these two realities and see them as one.

Images from left to right:

- Memorial for murdered protesters at Jackson Heights, Queens, NY 03/13/2021

- Cousin’s college graduation streaming on TV, Brooklyn, NY 05/22/2021

- Protest in Times Square, NYC, NY 03/20/2021

- Pencil drawing for architecture class, Brooklyn, NY 03/22/2021

- Posters for the first protest against the military coup, Brooklyn, NY 02/02/2021

- Protest at Foley Square, NYC, NY 03/27/2021

- Protest at United Nations, NYC, NY 02/02/2021

- Birthday dinner, Brooklyn, NY 02/17/2021

- Twenty-first birthday, Brooklyn, NY 02/17/2021

- Merchandise to raise funds for Civil Disobedience Movement, Long Island, NY 05/08/2021

- Zoom class, Brooklyn, NY 05/11/2021

- Protest at Times Square, NYC, NY 04/03/2021

- Dad’s Burmese Spring Revolution bazaar sign, Manalapan Township, NJ 04/17/2021

- At the car dealership, last day with our family car of 10 years, Brooklyn, NY 05/15/2021

- Protest at Brooklyn Bridge, NYC, NY 03/27/2021

- Cherry blossom outing, NYC, NY 04/24/2021

- Seeing news on the TV about the military coup for the first time, Brooklyn, NY 01/31/2021

- Memorial for murdered protesters at Jackson Heights, Queens, NY 03/13/2021

Who Knows the Arbitrariness of Being Born Some Place and its Magnitude

Juan Harmon, MFA, Poetry

Additional Information

Program

Announcing the Winners of the 2023 Migrations Creative Competition

We invited students to share essays, poetry, and art about the ways that migration shapes life in their communities. View this year's winners, and see how their work shows the connections between racism, dispossession, and migration in interdisciplinary, innovative, and impactful ways.

Jump to a submission:

À la République | From Darkness to Destiny | Returning to Nothing | What Freedom Was | We Live We Judge We Lie

À la République

Victoria Abunaw '24, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences

This piece was inspired by the sculpture Le Marron Inconnu, "the unknown Maroon." This sculpture once stood in front of the presidential residence in Haiti before the earthquake of 2010. It depicts a formerly enslaved man with shackles bound to his ankles, his limbs flexible and stretched out as he blows into a conch skyward. It is widely considered the preeminent symbol ofthe Haitian Revolution and post-independence resistance efforts against colonial powers.

As for À la République, it was envisioned as a response to its predecessor. Indeed, the struggle of our ancestors against a colonial past and continued poverty has not yet ceased; rather, it has taken a new form, sprung from the tribulations of the contemporaneous generation. The man gazes outward, but not at the viewer, with the conch just at his lips.

The colors used for the background are a subtle allusion to the flag of Haiti, which is red on the bottom and blue at the top. In the sky is a special constellation which represents liberation from enslavement and the shared heritage of the African diaspora, especially those of which arose during the trans-Atlantic slave trade; but the sky (depicted as outer space) also represents progress—a state which extends above and beyond the limits of earthly existence—the fruit of our progeny. It is futurity—the continued survival of Haiti and her people.

From Darkness to Destiny: A Migrant's "Mangaranto" of Identity, Education, and Cultural Resilience

Trifosa Simamora, PhD '27, Natural Resources and the Environment

The recollections of my past are etched in the vivid moments when my parents, amidst a power outage, in a city shrouded in darkness with closed shops, urged me to pursue my studies. The feeble glow of a lamp, fueled by a small wick and kerosene, became my guiding light during those blackout hours when I diligently tackled the homework I had been assigned that day at elementary school. The proximity to the flickering lamp left my nose tinged black from inhaling its darkened smoke. Although the day had long worn into night, my father persisted in his late-night labor, while my mother prepared fried snacks for the next day's sale. Their toil aimed at shaping the destiny of their offspring through education.

Hailing from the rich traditions of the Batak, one of the ethnic groups in Sumatra Island in Indonesia—with our own language and alphabet—my parents had long embraced the ethos of "Mangaranto” [sailing from place to place], a quest for a better life, leading them towards the flourishing island of Java, where progress and education were booming. Despite the move for enhanced opportunities, they steadfastly clung to their identity, always identifying themselves as proud members of the Batak tribe. They instilled the values and cultural essence of Batak within the family. I often pondered why education held such a profound place in their hearts, why we had to hit the books every night while our peers indulged in the latest TV shows, music, and news. Their response, "Metmetpe sihapor dijungjung do siman jujungna, metmet pe jolma dijungjung do baringinna" [like a tiny grasshopper lifts its head high, so should humans], a value that teaches us that despite limitations, one can uphold dignity through benevolence and responsibility. Unbeknownst to me then, my mother's own unfulfilled pursuit of higher education fueled her determination to ensure that my two siblings and I would achieve a better life through college.

As an adherent of a minority religion, I encountered taunts and mockery from peers, with my faith becoming the target of ridicule. Disheartened by the unfairness, I once faced a rowdy friend's harsh tirade. In silence, I absorbed the insults, recalling my parents' teachings of "Pantun hangoluan, tois hamagoan" [politeness brings life, arrogance brings disaster] underscoring the vitality of a genial attitude and the perils of hubris. This unfair treatment fueled my resolve to fight through achievements. I toiled industriously, securing admission to high school, consistently acing my studies, and proudly earning the title of class champion. All are driven by the conviction that hard work yields success. Supportive friends and teachers surrounded me, propelling my journey as the eldest child, commencing my personal Mangaranto by seeking education in a larger city.

Finishing high school years, I was accepted into a state university in Indonesia. I vividly recall my father escorting me to the university gate, where the welcoming words proclaimed, "Welcome, the best sons and daughters of the nation." A proud smile adorned my father's face as he wished me, "Good luck, the best daughter of the nation." Those words ignited a surge of pride within me, marking the commencement of over a decade away from my parents, navigating a migratory existence. I realized that in larger and modern cities, respect for others was paramount. My experiences from childhood, which were concealed in smaller towns, found expression through academic excellence and unwavering integrity on the campus—a reflection of the Batak values "Hasangapon" [dignity and honor] embodying nobility and dignity, and mitigating the "fear of difference."

Securing a scholarship for studies abroad posed formidable challenges, even facing opposition from my parents at one point. Acceptance into a master's program in the U.S. triggered trepidation as I commenced my education in 2021 amid the rampant COVID-19 pandemic and physical distancing. The events surrounding the murder of George Floyd further heightened concerns about the educational landscape in the U.S. Despite the initial fears, life in the U.S. unfolded as an opportunity to explore diverse cultures, forge friendships with individuals from various countries, and delve into the uniqueness of global societies. The marginalization I experienced in my youth fostered empathy for friends facing similar challenges. Upholding the Batak value of "Marsisarian" [mutual understanding and assistance in conflict situations], I found solace in the efforts of individuals and institutions to foster diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in U.S. higher education. The marginalized perspective instilled a profound appreciation for the depth beyond superficial labels, appearances, and accessories—an understanding that every human deserves respect and honor.

Upon completing my master's degree, I returned to Indonesia, where my parents beamed with delight. Yet, I recognize that my Mangaranto journey remains. Acceptance into Cornell evoked profound emotions of gratitude, a reality surpassing my wildest dreams. Excitement overwhelms me as I acknowledge the continued opportunity for further education. Practicing the Batak value of "Hamajuon" [progress to enhance competence], I realized that my migratory journey is the mixture of personal aspirations along with the pervasive influence of my family's strong Batak culture. The journey has intertwined my personality with a myriad of values, and every new destination offers lessons in shaping my evolving identity. An Indonesian proverb, "Di mana bumi dipijak, di situ langit dijunjung" [wherever on earth you tread, the same sky is being upheld] underscores the importance of respecting local customs, a belief that the virtues we carry from our culture contribute positively to the communities we encounter, enriching our shared society.

In essence, my journey encapsulates not only personal growth but also the collective progression of embracing diversity, fostering inclusion, and upholding mutual respect across borders. Each chapter adds a layer to the narrative, emphasizing the interconnectedness of cultures and the richness derived from understanding and honoring one another. As I navigate my path, the values instilled by my parents and the Batak traditions continue to guide me, urging me to contribute to a world where differences are celebrated, and unity prevails.

Returning to Nothing: Migration and Displacement from the 2022 Floods in Pakistan

Tabindah Anwar, MA ’24, Global Development

Anwar took all the photographs included in this essay during their fieldwork in some of the worst flood-impacted districts in Pakistan in 2022.

Climate disasters weaken social structures and exacerbate existing inequalities. In 2022, Pakistan was hit by one of the worst floods in decades, where more than 33 million people were impacted. And nearly 8 million people, a population almost the size of New York City, were internally displaced.

These nationwide floods occurred as a result of unusually extreme monsoon rainfalls. “Screams of people woke me up,” said Yasmeen, a 28-year-old woman who lived in a valley in the northern mountains of Pakistan. The torrential rains and forceful gushes of water down the mountain ridges destroyed everything on its way, including houses and farmlands, and killed thousands of livestock. With only the clothes left on their bodies, Yasmeen and her family rushed to find shelter in the nearest village.

In rural areas, livestock and agricultural produce are sources of food and income for people. Even if their houses are reconstructed, it would take several years for Yasmeen’s family, and many others like them, to recover from the loss of livestock and crop damage.

Meanwhile, thousands of miles southwards in Balochistan, Laila, a young mother of four children, explains the terror she felt when carrying her children to a safe location during the flood. "One of my children has a hearing impairment, and she froze with confusion," said Laila.

Laila’s husband farmed on leased land, and their source of income was from selling the harvest. Their wheat crop was destroyed, and with the standing water in the field, there were no prospects of sowing for the next season. Already poverty-stricken, Laila’s husband had no choice but to migrate to the nearby urban center to find work and a daily wage. Laila was left behind, taking care of her children alone, as she took temporary shelter in a relative’s home.

Displacement due to climate disasters and migration to revive the livelihoods weaken a family unit and the social structure. The families are forced by their conditions to split up, where the male members of the family, including the father and the elder son, move to an urban center for a daily wage. Women are responsible for agriculture, caring for the livestock, and raising their children alone. There is immense pressure on them, and the responsibilities are many. With that, they cannot send their children to school, especially the female child, who is usually helping the mother out.

Political displacement and climate displacement can have compounding effects on people’s resilience to cope with disasters. Pakistan’s former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), a region that also borders Afghanistan, has Afghan refugees and internally displaced communities from the aftermath of decades of militancy and terrorism in these areas. In recent history, these areas were merged with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan for better economic integration of the local communities. With existing precarious economic conditions, when the floods hit this area in 2022, many Afghan families who had fled the Taliban takeover in August 2021 were displaced again. Many did not have legal documentation or refugee cards, so they had trouble accessing social services in their host country.

Mehr, a village in the southernmost part of the country, was one of the many submerged areas during the floods. Sumaya, a local woman, shares the agony of escaping on a boat while being heavily pregnant. With most of their belongings destroyed and their animals killed, families took their remaining livestock with them on fishermen's boats to the nearest dry area.

If lucky, families would find camps, but most lived in the open air without shelter from the cold or the mosquitos. Women had no privacy, they had to defecate openly, and a few even gave birth while living on the campsites. People lived in these conditions for more than two months, and as the water receded, they returned to their villages to rebuild their homes. These families have fallen into the vicious cycle of poverty, and relying on the government’s meager social support is their only hope to make ends meet.

The increased uncertainty due to migration and displacement means losing resilience and agency, which leads to increasing reliance and dependence on social services and humanitarian aid. However, not everyone impacted by a disaster can access social services equally. A woman-headed household living on a campsite will face more constraints in reviving their lost identity documentation and accessing social support. This exacerbates and reinforces inequalities.

People at the front line of the impacts of climate change are often already vulnerable and poor and rely on subsistence farming and animal herding as a source of income and food. These communities have not contributed towards climate change, yet they face a heavy brunt. This is a form of environmental injustice. The perspectives of the climate-vulnerable communities should be voiced in our academic and policy work so we can meaningfully advocate for those communities struggling to build resilience after being displaced.

What Freedom Was

Rachel Friedland '25, Human Biology, Health, and Society

Freedom was the shoebox apartment on Orchard Street

With white voile curtains and mismatched chairs

Hot concrete on the balls of his feet in the summer

Weaving through pantlegs looking for his mother

Peddlers and pushcarts and mangoes and pears

Freedom was three cots on the kitchen floor

Splintering planks that complained and groaned

One couch and one bed shared by nine

A window mooring the end of a clothesline

Tethering families adrift from home

Freedom was the first two candles on the windowsill

Lighting a life that was forced into shade

A fist of sweet bread and small cup of wine

His belly of hope that here we’d be fine

To pray and to laugh and to sing unafraid

But freedom was not.

Six nieces and four cousins killed naked

Two brothers lost in the fight overseas

The newsstand he opened on Delancey

A hotbox of headlines

He carried a gun

Freedom was his great granddaughter studying biology

In a university library eyes glued to a screen

Biting her tongue while she unraveled thread

Students in her classes wanting her dead

No, freedom was not what he thought it would mean.

We Live We Judge We Lie

Inae Kim '27, Landscape Architecture

We always pull up our phones to know about each other, for example, trading phone numbers, social media, or text. I felt like people these days judge and look at others through their phones. The monster in the drawing has iPhone camera eyes instead of regular eyes.

People hurt each other even when they do not mean to. The hand in the drawing is trying to pet the cat, but the cat is offending the hand. This shows the unparalleled intentions of approach to each other.

Additional Information

Program

Conditions Are Getting Worse for Immigrants Detained in Upstate NY

Jaclyn Kelley-Widmer, Migrations

In this op-ed, Cornell Law professor Jaclyn Kelley-Widmer (Migrations) shares firsthand insights into the conditions immigrants face when detained in Upstate New York.

Additional Information

Undergraduate Migrations Scholars

Details

Join our team of undergraduate Migrations scholars to think in new ways about global migration challenges and understand our world on the move. As an undergraduate Migrations scholar, you'll play an active role in migration-related scholarship and programming on campus.

With the support of Migrations Program director Katie Fiorella and our cohort of graduate fellows, you will explore key issues in migration studies and build leadership skills alongside a cohort of your peers. In the spring semester, scholars will have a chance to plan an event on a migration theme of their choice.

Last spring, our cohort of Migrations scholars hosted two events featuring panels of migrations faculty and human rights organizers:

- Margins and Mobilization: Migrant Worker Precarity and Power in the Trump-era Economy

- From Colony to Diaspora: Enduring Legacies of U.S. Territorial Rule in Puerto Rico and the Philippines

Eligibility

All undergraduate students who are interested in migration studies are encouraged to apply. Previous Migrations scholars are welcome to apply again.

You should be in good standing academically and have no unresolved disciplinary charges or sanctions, be enrolled in an undergraduate degree program at the time of the fellowship (e.g., not on leave of absence), and be on campus in Ithaca for in-person meetings and mentoring.

Deadline

September 30, 2025

Amount

Students can elect to enroll in a one-credit course or receive $250 upon successful completion of the fellowship in spring.

How to Apply

Fill out the online application. The application requires you to submit a short paragraph (250 words) about why you want to be a Migrations scholar and your resume or CV.

If you have any questions, contact migrations@einaudi.cornell.edu.

Additional Information

Information Session: Global Research Fellows

September 11, 2025

4:30 pm

Uris Hall, G08

Global Research Fellows are a new interdisciplinary research and professional development community at the Einaudi Center for advanced graduate students, Cornell postdocs, and visiting and local scholars. You'll find a community of fellow researchers with regional and international interests and a desire to foster a more equitable world.

Eligible students:

• Have completed at least two years of graduate education

• Engaged in research on a topic of global or regional studies significance

• Hold a strong desire to impact global challenges and create real-world solutions

• Interested in engaging and collaborating with other researchers

Can’t attend? Contact programs@einaudi.cornell.edu.

***

The Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies hosts info sessions for graduate and for undergraduate students to learn more about funding opportunities, international travel, research, and internships. View the full calendar of fall semester sessions.

Additional Information

Program

Einaudi Center for International Studies

Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies

East Asia Program

Southeast Asia Program

Latin American and Caribbean Studies

Institute for African Development

Institute for European Studies

South Asia Program

Migrations Program

Southwest Asia and North Africa Program

The Production of Climate Mobility Futures: Comparative Insights from National Security Strategies

November 20, 2025

12:00 pm

Register for the virtual talk here: https://cornell.zoom.us/meeting/register/9scDvJ8BTNqY2h1Z4_o2Vg.

Climate change deteriorates habitability. How will people respond who inhabit the affected spaces? (Im-)Mobility is one of the most prominently debated behavioral responses. Importantly, there is little scientific support for the claim that environmental deterioration by itself results in international mass migration. There is, however, good evidence that migrants are vulnerable to climate change impacts during their journeys. This paper explores the extent to which the notion of future, inevitable large-scale, climate-driven, South-North migration prevails in official positions – despite these nuanced findings. To this end, the paper takes stock of how national governments frame these futures in their national security strategies. The paper discusses framing differences between countries that typically receive migrants and those that are typically countries of origin. Governments, particularly from the Global North, frame migration often as an inevitable function of climate change. They do refer to migrants not as victims of this breakdown of sustainability or as protagonists of adaptation – but as the drivers of breakdown of peace in destination countries. In closing, the paper points to framings that are more aligned with the state of scientific research and that are more conducive to a sustainable, peaceful response to potential climate-related displacements. More generally, the observed framing of climate-related mobility is a textbook case for counterproductive framings of climate-related insecurities. If not well aligned with research, such framings risk justifying unsustainable policies that prioritize reactive means and the securitization of national space over ambitious climate policies that aim for long-term human security and sustainability.

About the speaker

Dr. Anselm Vogler is a Non-Resident Fellow at IFSH since February 2024. Until recently, he was Postdoctoral Researcher at Harvard University, Cambridge, USA and, prior to that, at the Department of Geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In 2024 he successfully defended his dissertation on climate security policies. From April 2020 until January 2024, he was research associate at IFSH and worked in the DFG cluster of excellency Climate, Climatic Change, and Society (CLICCS) at University Hamburg. Anselm Vogler studied political science in Dresden and New York. He was awarded an International Recognition for his dissertation by the Hans Günter Brauch foundation as well as the Viktor Klemperer Medal for distinguished success during studies and an award at the Beijing-Humboldt Forum.

Host

Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, part of the Einaudi Center for International Studies

Register for the virtual talk here: https://cornell.zoom.us/meeting/register/9scDvJ8BTNqY2h1Z4_o2Vg.

Additional Information

Program

Einaudi Center for International Studies

Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies

Migrations Program